In two strikingly different cities, Paris and Chicago, we can trace the logic of the modernization of urban space to the contemporary Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO). In Notes from The Expanded Environment; Chicago Union Stockyards: a Genealogy of the Feedlot, we visited Baron Haussmann’s most recognized and arguably most controversial modernization plan in Paris. The plan was approved, in part, because the city housed nine separate slaughterhouses. These works became a public health issue that ushered in a new set of spatial governance strategies. Mechanized refrigeration, a boon for public health advocates, allowed for the decentralization and eventual demise of the Chicago Union Stockyards. In both Paris and Chicago, the urbanization of animal slaughter was closely tied to the accumulation of knowledge and evolving conceptions of urban space, especially the emergence of the public-hygiene movement. Meat-packing companies transformed labor conditions that reverberated throughout the economy. Production was sped up by the invention of the “disassembly line,” a precursor to Henry Ford’s better-known version. The refrigerated railroad car, coupled with more efficient labor methods, altered transportation and market networks and invented novel business strategies through the meat by-products industry.

The Stockyards were very much a product of their supply chain and were dependent upon the production of perishable commodities. Transporting live animals (“on-the-hoof”) to markets required herds to be driven up to 1,200 miles to railheads in Missouri where they were loaded into stock cars and transported to regional processing centers. Driving cattle across the plains caused tremendous weight loss, with some animals dying in transit. Inefficiencies were costly and inherent in transporting live animals by rail because sixty percent of the animal’s mass became inedible. Farming began to push even further outward from the city as suburbanization occupied the interstices. Refrigeration and motorized transport allowed for stockyards to be closer to the farm.

The first mechanized refrigerators were engineered to cool entire warehouses with ice, but this practice was inefficient, unsanitary and occupied too much space on the warehouse floor. The icebox on wheels was the first consignment of dressed beef that left the Stockyards, in 1857. Ordinary boxcars were retrofitted with ice bins utilized for cooling. The temperature-controlled carriage allowed corporate enterprises like Swift & Company, and Armour & Company to ship their products across the United States and internationally. Logistics firms became innovators for the early mechanical refrigeration industry, giving way to national markets that revolutionized the meatpacking industry.

It wasn’t until the 1890’s when the American rights were obtained for a German patent for mechanical refrigeration, as these models were initially imported for breweries in Milwaukee and later tested at the the Stockyards. Like The Stockyards, The Hercules Iron Company’s Cold Storage Building was a feature at the World Columbian Exposition, 1893. People flocked to The Stockyards more than any of the Exposition’s attractions, so by proximity, attendees were eager to experience the potential of cold storage. It was shortly before the opening of the Exposition when the cold storage facility caused a gas explosion, killing 17 people. Many related tragedies continued with the rapid expansion of refrigeration equipment into the early 20th century. This problem eventually led to the development of freon, an artificial refrigerant with known effects on the ozone layer, discovered many decades later.

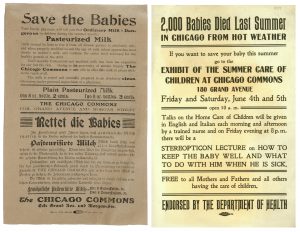

By 1920, the Swift Refrigerator Line (SRL) owned and operated 7,000 ice-cooled rail cars. The General American Transportation Company would assume ownership of the line in 1930. Refrigerated rail cars became devices to protect the public and contain street pollution, while at the same time, they aided the state in its quest to gain control over its population, modes of production, and acts of killing. Climate control takes on many meanings here. Profit motives, deployed through climate control models such as refrigeration and pasteurization, also manifested itself in a superficial concern for hygiene conditions in the city. The close relationship between consumption and death made slaughterhouses emblematic of the rise of mass-production and the spirit of science, technology, and state politics. There was a peculiar mixture of morality, social welfare, and environmental control, while the health of humans and the cleanliness of urban environments became a central organizing ethos. For instance, the fatal combination of unpasteurized milk derived from The Stockyards combined with the heat wave of 1908, killed 2,000 infants in the heavily polluted south side. The Infant Welfare Society was established shortly after in 1911. The spatial production and delineation between the human and nonhuman, etched firmly into physical infrastructure, was effectively the foundation of an emerging biopolitical industrial society.

In the latter half of the 20th century, in a decentralizing post-war economy, structural changes to both the meatpacking industry and national infrastructure began to alter the packing industry by the 1950s. The advent of the interstate highway system and the refrigerated trucks meant that livestock breeders no longer had to ship animals by rail to centralized urban locations. Packing plants could relocate nearer the source of the livestock in the rural Midwest, South, and Great Plains. New smaller packing companies took advantage of these changes to erode some of the market share of the traditional packing companies (Swift, Armour, Wilson, and Cudahy). New, modern, efficient one-story plants were compliant with increasing governmental regulations, such as those which required more humane slaughtering techniques. Multi-storied plants in cities like Chicago were too expensive to update and were made obsolete. The Big Four packing companies, had no choice but to remain competitive and abandon Back of the Yards.

Whereas railroads had fostered centralization, now truck transport promoted decentralization and the search for cheaper locations in the countryside. And finally, urbanization itself was becoming an obstacle. The Stockyards continued to decline for the next few decades, and by the 1970s, neither Paris nor Chicago operated slaughterhouses anymore. Tucked away in the countryside, animal slaughter has truly moved out of sight. The post-industrial age witnessed the demise of the modern mass-slaughterhouse because it did not fit into the image of the so-called postmodern city. All over the world, former slaughterhouses are now being reclaimed by urbanites, who are appropriating them for other purposes. Madrid’s largest slaughterhouse and cattle market, in the Arganzuela district, the Matadero Madrid is one of the most enduring and singular industrial establishments of 20th-century Madrid. Production halted in the 1970s. In 2005, work began on new projects at the direction of the Arts City Council of Madrid. The Matadero complex for contemporary artistic production houses a number of examples of what has become known as New Madrilenian Architecture. Cities from Buenos Aires to Frankfurt are partaking in the slaughterhouse revival and meat-market districts in New York and Chicago have been transformed into trendy loft neighborhoods, reinventing the slaughterhouse as an aestheticized space for consumption and entertainment.

Transparency, once being the rallying cry of animal activists, has been reappropriated into the meat industry. Fair Oaks Farms, in Northwestern Indiana, is a prime example of slaughterhouse-as-amusement-park. Tourists come from far and wide to gaze at the contemporary technologies of dairy and meat production. Glass walls separate the smells and sounds of the feedlot while privileging the image. What is seen is choreographed, narrated, and packaged as bucolic and personalized for the viewer. The meat industry has appropriated the anxieties of animal-rights activists as a new design initiative. Fair Oaks Farms can simply hire someone with design expertise, just as prisons hire architects to design execution chambers, or the appropriation of psychotherapy in military “enhanced interrogation techniques”. For instance, the work of Dr. Temple Grandin operates within the processes of animal engineering by claiming an affinity with the non-human through the moniker of humane practices (and does not address larger epistemological issues). Grandin’s development of the Chute which allows animals to remain calm on their way to slaughter is another technique of soft forms of violence and control. It is my claim that the production of animal subjugation in the industry, from Upton Sinclair’s Jungle to ultra anesthetized modern German animal husbandry models, has essentially remained just as problematic as it always has. The meat industry conflates marketing and architectural design to convince the public that it is possible to kill congenially at an industrial level.

Industrialization and modernity brought predictability into focus (from a market, and scientific point of view) and emphasized the importance for civilization in agricultural improvements, equating progress and quantity with scale. The industrialization of agriculture was a complicated transition from traditional to modern that involved individual farm families, the states, new agricultural experts, bankers, economists, engineers, journalists and manufacturers, all playing a roll in the postwar consciousness of the factory farm. The rationality of industrialization carries disembodied scientific rationale through time and space. While the bucolic countryside is still there, many farmhouses and barns sit empty. Some sectors moved to the contemporary Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO), a place that feigns modernity while masking the true brutality of the modern and merely pushing around problems. And the public health crisis continues, yet without an easily connectable politics of visuality. Automated confinement systems more and more control food and reproduction, climate control and life capacity. The controlled, choreographed interiors of the CAFO performs as forced ecologies and life support systems while operating as porous membranes within the larger ecology.

Supposedly empty spots on the map fill up with land use intensification, new kinds of infrastructure, environmental and social impacts rendering them in a complex relationship to types of urbanization. The rural is increasingly being transformed into a networked operational landscape.