Recently this article appeared in the 101st edition of Topos Magazine. Rather than paying 135 Euros (way too expensive!) can you download the full article here. Enjoy!

Currently there are roughly 163 million pets in the United States. Approximately 44% of all households in the United States have a dog, and 35% have a cat. Said another way, that’s nearly 1 pet for every 2 humans in the USA. And while pet ownership is popular and likely on the rise, our interaction with animal life in general is increasingly prescribed, controlled and in decline. But this has not always been the case and is in fact contrary to the bulk of human history. Not all that long ago, animals and humans – though, we’re really animals too – intermingled closely through-out the day in our public and private lives. Cities were filled with non-human life: horses pulled trollies, street carts and wagons down urban streets, pigs, chickens and other fowl were kept open in small city plots, pets and domesticated animals roamed the neighborhoods. The great cities of the 18th and 19th centuries like New York, London, Paris and Berlin, were rife with animal life. Between 1718 and 1914 the number of London cows grew from 6,000 to over 20,000 at its peak in 1852, and then dropping slightly to 18,000. Similarly impressive figures can be found for other animals: 200,000 horses in London at the end of the 19th century, and a great many other hundreds of thousands of pigs, sheep, fowl or others.

Animal Cities

The Georgian and Victorian city was filled with a constant animal presence in almost every aspect of city life with all of the accompanying sounds, smells, blood, guts, and frankly disease-inducing conditions. But by the 19th century things began to change. City planners had taken a proactive attitude towards reducing animal waste in the urban centers and popular attitudes towards cleanliness, miasma and disease were also changing. The presence and popularity of the newly built London Zoo was further indication of a growing trend of separating and reconsidering animal life and value in the European city. And by the start of the second world war most animal life had been dramatically reduced in European cities. In Paris for example, the horse population plummeted from 110,000 in 1902 to 22,000 in 1933. Today’s cities, not only Western but cities in general, have almost no animal life in their cores, and if they do, it is strongly curtailed.

But perhaps this is all soon to change. Despite the century long trend of declining urban animal life there is an increasing desire among many designers, planners and thinkers to re-introduce an animal presence in our contemporary lives and cities. Driven by the growing threats of climate change, population boom, and rising species extinctions their projects ask: “How can we co-exist with a greater bio-diversity in denser, more populated areas?“ and “What are the benefits of animal cohabitation, and what are their messy, less romantic consequences?“ Several strategies have presented themselves: Co-species Cohabitation, Urban Agricultural projects, and Urban Greenscaping each offer new and varied lenses through which we can start to rethink of living more closely with our animal counter-parts. Some of these are a reawakening of dormant ideals, some are indeed boldly avant-garde.

Co-Species Cohabitation

Living in closer proximity with our animal companions, as any devoted pet owner will tell you, is a foundational, loving and transformative experience. And there are numerous benefits to living with pets: decreased stress, decreased blood pressure and levels of cholesterol and triglycerides, as well as decreased feelings of loneliness. Overall pet-ownership results in increased longevity, and desires for physical activity and socialization (https://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/health-benefits/). If we can happily coexist with dogs and cats, why not racoons, owls or squirrels? Though the thought of inviting “pests” into our homes might strike some as off-putting, several designers are proposing just that – if not quite to the extent of our domesticated companion species. The works of two architects Sarah Gunawan, and Joyce Hwang stand out in this field for their beguiling and sensitive invitations to non-human life.

Sarah Gunawan, currently the Reyner Banham Fellow at the University of Buffalo, NY developed her Graduate thesis at The University of Waterloo, titled “Suburban appendages” to address synanthropic species in the typcial North American suburb. In her thesis Ms. Gunawan displays an array of ways in which the average Canadian or American home can be host to more than a nuclear family. In the proposals shown here, a small roost is constructed on the home for nesting barn owls, bats are invited to hang-out between wooden slats along an exterior wall and a population of racoons are invited by helping to aerate and distribute compost while foraging through residential waste. Moreover the project suggests that these non-human activities can be symbiotic, not only benefitting the human inhabitants but the other animal lives. In this newly outfitted animal-centric suburb compost-turning raccoons keep a chimney-flue warm for a population of swifts, insects drawn to the residential waste become food for the bat population and owls feed on smaller rodents. Each action creates an interlinked and interdependent world – a web of animal life.

Joyce Hwang, Director of the experimental practice Ants of the Prairie and Associate Professor of Architecture at SUNY Buffalo, has developed several built animal-centric designs. Two projects “Bat Tower” and “Bat Cloud” also show how successful animal habitats can be when designed for symbiotic uses: In “Bat Tower”, an installation outside of a park in upstate New York, native plants known to draw insect life are encouraged to colonize a structure for roosting bats. Similarly “Bat Cloud” elevates a planted garden in the tree-canopy to provide food and roosts for local bats.

Urban Agriculture

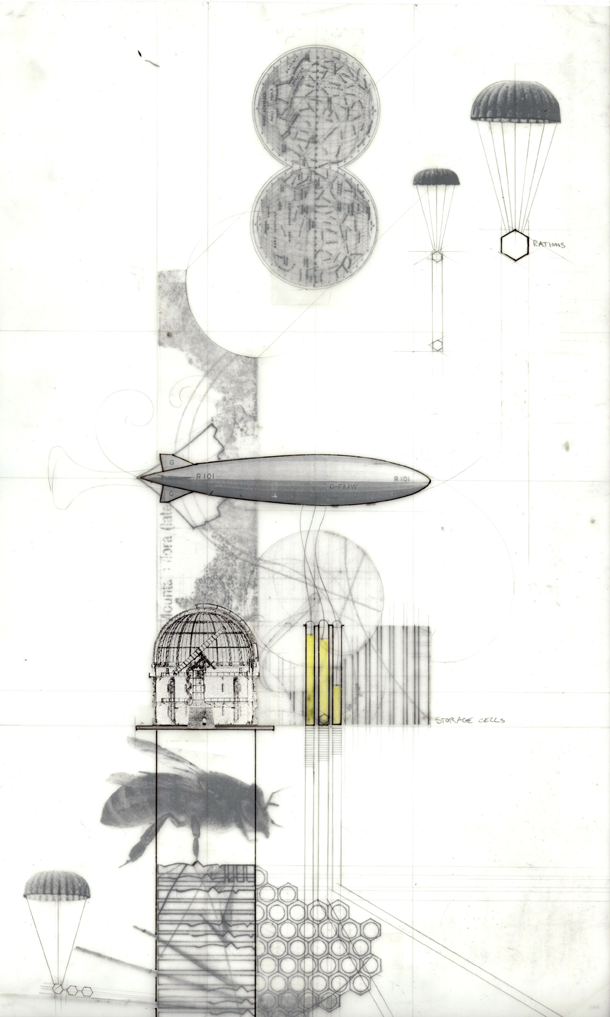

But clearly, other than a personal, emotional or ecological benefit, the main reason that people have lived with other animals is agricultural. Again, the period in western cities from the 17th to 19th centuries seems an aberration of human history: Throughout the majority of human civilization the garden has been a central and arguably centralizing part of normal life. But as the large metropolitan cities of the 18th century modernized and densified, agricultural activities were driven further and further out, and the small urban garden disappeared. But more and more designers are harvesting the potential of urban agriculture in their designs, for instance Carey Clouse and Zach Lamb with Crooked Works. Clouse and Lamb, partners in the Massecheusets-based Crooked Works and both Architects by training, address the tough issues of urban identity, food security, and environmental stewardship through design interventions. Their projects “Cart Coop” and “Window Unit” re-envision the domestic life with food producing domestic animals. In “Window Unit” fish, chicken and bees are each positioned within reach of the kitchen. “Cart Coop” transforms your basic shopping cart into a sophisticated chicken roost, repurposing a discarded commercial tool and suggesting a kind of literal farm-to-table approach to farming where one can push a mobile coop right to your doorstep. Still, many other architects or landscape architects are designing apiaries on urban roof tops, raised planter beds and indoor hanging gardens.

Urban Greenscaping

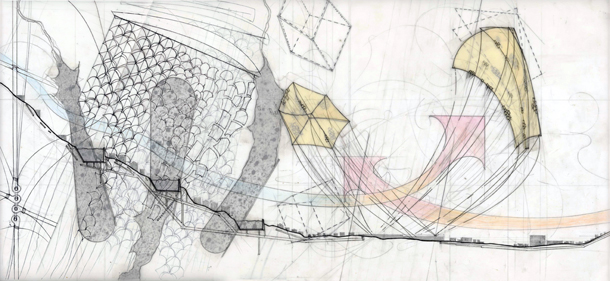

One line of thinking and an increasingly popular strategy to promote animal life in our urban cores views the city, as a whole, as a place for increased bio-diversity. For decades, a pervasive sense that “nature” does not exist in city centers has dominated how we define animal life in and out of cities. But a growing group of landscape architects, ecologists and planners, bolstered by increasing scientific studies in Ecosystem Services, are changing this perspective. They argue that animal life indeed already exists in urban centers and can in fact flourish there. Urban Landscapes, rather than commingling the human and animal spheres as closely as in the above, aim to achieve a kind of pan-species balance between our built and unbuilt environments. These are projects that generally seek to soften urban infrastructure and to create “green ways” in, around and through metropolitan areas. Many of these projects are large-scale landscape projects like “Arc Wildlife Crossing” located along I-70 in Colorado’s Vail Pass, the acclaimed “Highline“ in New york City and Houston’s “Buffalo Bayou Park”, a beautiful, snaking greenway through the heart of a major urban metropolis. But Urban Greenscaping interventions can be smaller – working at the scale of a bird house, a bee hive, an insect hotel, or a bird perch. The works of the Houston-Based Expanded Studio (full-disclosure this is the author’s design practice), the London-based 51% Studios and Lisa Lee Benjamin’s Zurich based studio (image above) are all represenative examples of the myraid ways in which small-scaled interventions can be deployed within the built environment to encourage animal colonization.

Human Animalism

There is yet another way of approaching this discussion of alternative-species roommates. And that is through the lens of post humanism – or rather, through our own and generally neglected animalism. There are two basic truths here: First – we are already animals. Second – we are also already multiple animals. Even alone we already have room mates, permanent roommates. Our bodies are home to millions of micro-organisms that are certainly not human. The micro-biome in our stomachs and intestines is probably the best example of these symbiotic house-mates. But there are countless other mites, bacteria, and small organisms that make human life possible. We are all of them. From this perspective the idea of living with other animals is a centrally human condition. In fact it would contradict a key part of our humanity to not recognize non-human lives in our world. Artists, designers and architects working in this field show us a new, or neglected side of our humanity and offer that in a posthuman world, a world where possibly humans recognize that they are one of many many key species that a truer sense of cohabitation could be achieved.

Designer and Architect Simone Ferracina’s Theriomorphous Cyborg for example offers a human user the ability to enter into the animal world of a pigeon or a mouse. Sense perception would be reorganized according to the animal of choice and the world would appear to be a very different place. “In praise of dust” a student project by Young-Tack Oh, and a recipient of the 2015 Expanded Environment Awards, celebrates the microcosm of microbial life in a series of architectural ornamental designs. Similarly, the work of Brandon Youndt, an LA based Designer focused on the coexistence of animals and architecture, illustrates ethereal worlds where traditional boundaries of animal/human, animate/inanimate, are transgressed reshaping human and animal perceptions of the environment.

Future Thoughts

Architecture, cohabitation and animal life are not your typical bed-fellows – or at least haven’t been in the western world for the last century. After peaking in the 19th and 20th century animal populations in urban life quickly declined and the animals themselves have been continuously marginalized since. But, while we grapple with cataclysmic ecological events and as the world population soars to new heights, how we relate and inter-relate to other animal life will become critical to our own survival. Whether its living more closely with a greater variety of synanthropic animals or by understanding ourselves to be more complexly animalistic, our future will depend on the value we place on a rich and vibrant urban ecology. Should we return to a time where horses pulled trollies and pigs roamed the streets? Perhaps not…but should we marvel and encourage other life into our urban cores – a coyote, a hawk or a moose? Maybe that’s not so bad.