Many occupied regions of the world are turning arid due to rapid changes in global climate. This is causing the displacement of entire ecosystems, including the nonhuman and human inhabitants of the regions. In the middle-east especially, extended drought is leaving communities and neighboring cities without food or means of survival1. This desertification, along with the climate of war and political turmoil, is leading to a massive outpouring of refugees. Global political trends in policies are shutting off many safe regions from refugees, forcing them into periods of extended migration. The Bible suggests that similar refugees out of Egypt wandered through middle-eastern deserts for forty years, surviving on nothing but mysterious manna that appeared on the ground every morning. Perhaps there is a similar substance that can provide for modern refugees who wander through landscapes desolated by climate change and war. Aeroplankton might be such a substance, with potential to be harvested, processed into food, water, and cultivated into nomadic ecosystems hosting human and nonhuman migrants.

Aeroplankton is described by biologists as the atmospheric equivalent of marine plankton. It is a dense mass of tiny organic particulates from a multitude of different sources being blown around the atmosphere on strong winds. The atmospheric ‘soup’ is composed of insects, spiders, seeds, pollen, mosses, microbes, and thousands of species of bacteria and fungi2.

Aeroplankton visible to the eye in evening light (Photo via Wikimedia Commons).

Aeroplankton visible to the eye in evening light (Photo via Wikimedia Commons).

It is noted that aerial plankton, unlike marine plankton, has not been exploited by evolution, and therefore the sky remains one of the only niches of the habitable planet that large organisms have not evolved into3. The plankton of the ocean sustains millions of species, including massive whales, many of which flourish solely on the soup of plankton. However, very little life has evolved to feed on aeroplankton. Flying species such as birds and bats might periodically feed on the larger specimen, but inconsistently. Most of the airborne soup remains untasted and unknown, and there is no aerial equivalent of the whale, soaring through the sky with an open maw, gulping down the plankton of the sky.

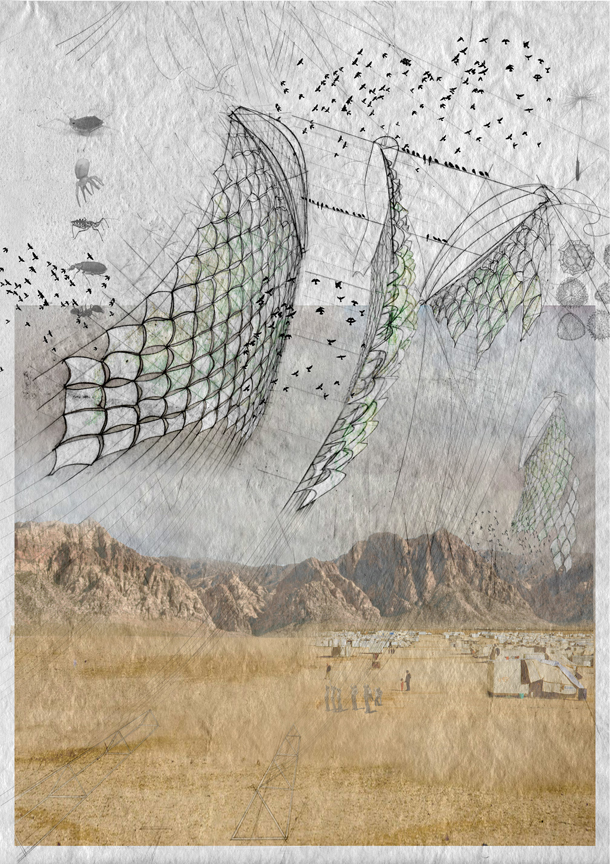

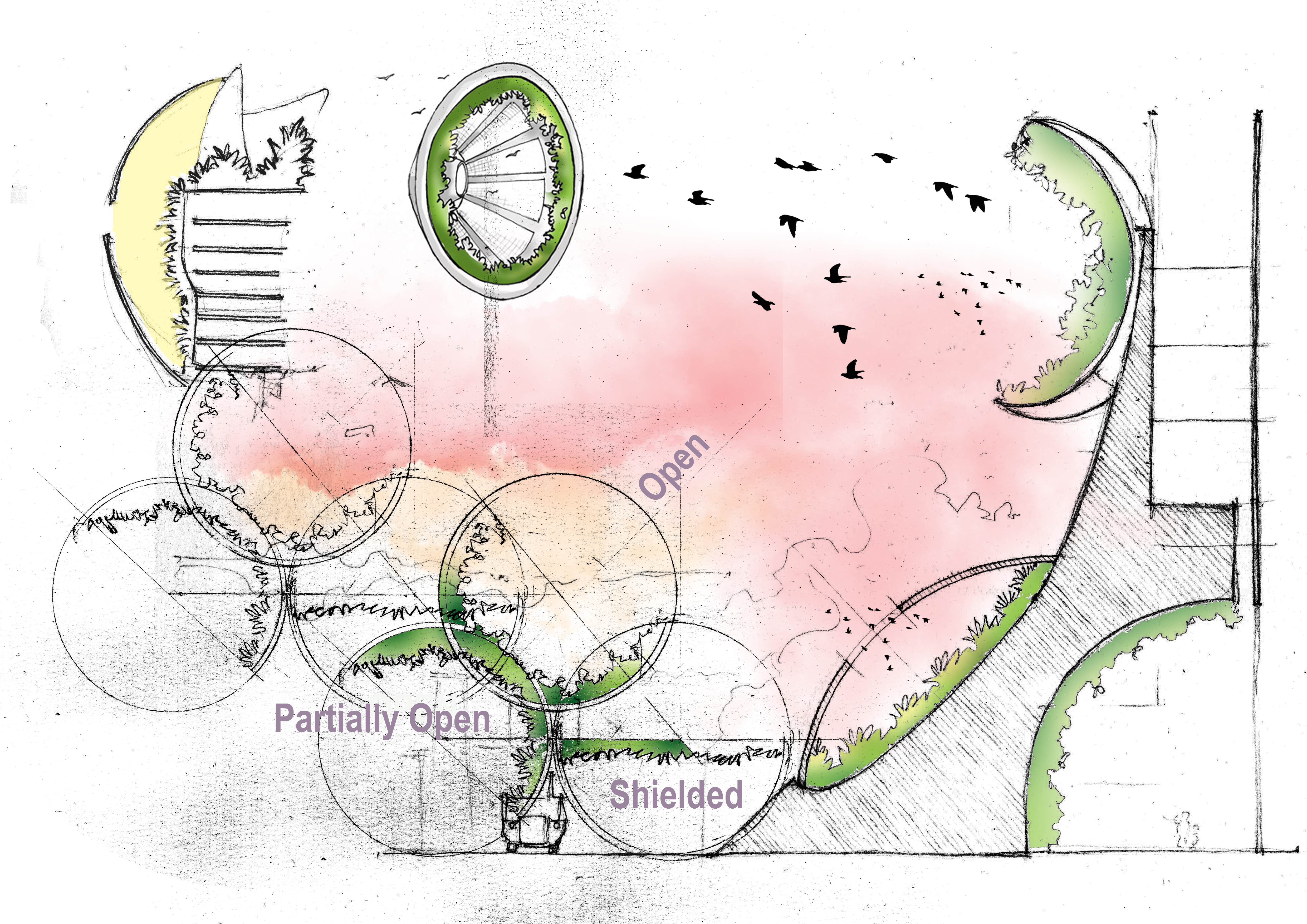

Humans could be among the first species on earth to occupy this realm and open up the use of aeroplankton to the broader evolutionary world. The top image suggests kite harvesters, collecting aeroplankton into aerial ecosystems for nomadic humans and non-humans. A single kite structure can harvest a multitude of aeroplankton, providing a haven from the ceaseless wind where they can feed and propagate.

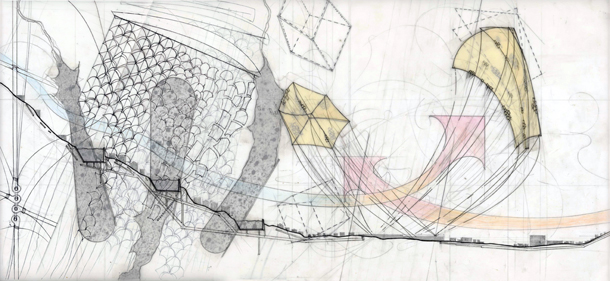

Drawing brainstorm of kite herd in areas of resource disparity.

Drawing brainstorm of kite herd in areas of resource disparity.

A herd of these kites can start to resemble an airborne garden, forest, or field, depending on the needs of the migrants. The aeroplankton swarm can be used as fertilizer or be engineered to meet various other needs. Birds that are drawn to the herd provide food for hunters and act as allies in locating other sources of food and water. Individual kites provide tracking information for refugees seeking each other, and herds spotted from the ground provide refugees with useful information regarding the environmental and political atmospheres of a region. Individual kites can also break from the herd and seed remote locations with biological ingredients, in hopes of repopulating desertified landscapes.

Buckminster Fuller’s Cloud Nines (Photo via Wikimedia Commons).

Buckminster Fuller’s Cloud Nines (Photo via Wikimedia Commons).

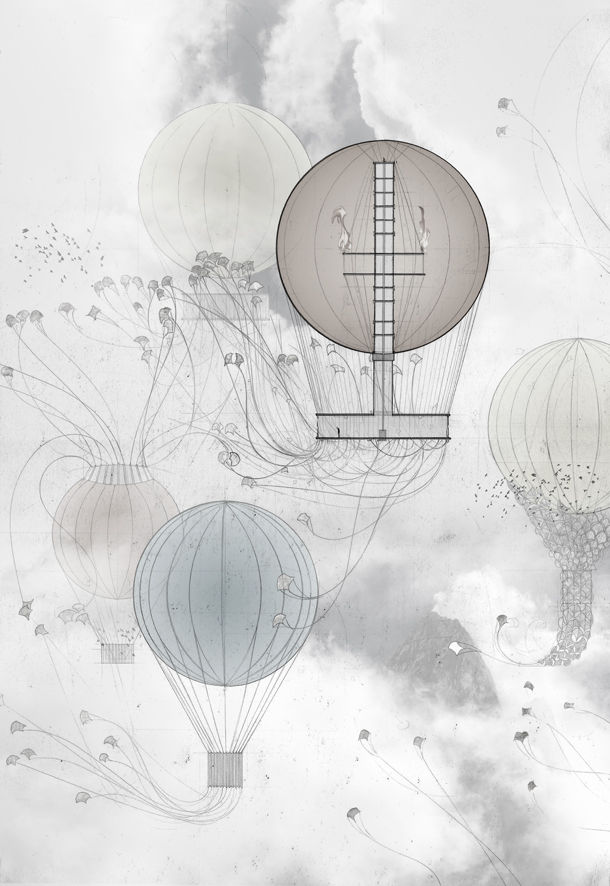

Buckminster Fuller suggested the possibility of massive airborne colonies that contain a great number of occupants. Some suggest that the force keeping the colonies afloat is the biological heat produced by the human bodies within – a hot air balloon, with each human body as a burner4. Perhaps it is not just human bodies, but microbial processes of harvested aeroplankton, and the other species that are drawn.

Migrant colonies sustained by the harvesting of aeroplankton and the resulting ecosystems created.

Migrant colonies sustained by the harvesting of aeroplankton and the resulting ecosystems created.

The above image suggests that such airborne communities could host human and animal migrant populations, harvesting aeroplankton to sustain various ecosystems. The colonies are kept afloat by the heat produced by living bodies, the uplift of strong high winds, and also the various processes of microbial life, and the heat produced from turning this plankton into sustenance.

1 Benjamin I. , , , , and “Spatiotemporal drought variability in the Mediterranean over the last 900 years”, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 121 (2016) 2060–2074, doi:10.1002/2015JD023929.

2 A. C. Hardy and P. S. Milne, “Studies in the Distribution of Insects by Aerial Currents”, Journal of Animal Ecology, 7(2) (1938), 199-229.

3 Richard Fortey, Life : A Natural History of the First Four Billion Years of Life on Earth (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998).

4 David Gissen, Subnature : Architecture’s Other Environments (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009).