Climate change is provoking a massive migration among humans and non-humans. As temperatures and weather patterns shift, entire ecosystems are being displaced. The displacement of nonhuman species spills over into human populations. Coastal and island communities are losing their food supply as the warming oceans drive marine life to cooler waters; while rising sea levels and increasingly severe storms erode the coasts. Droughts and floods leave inland regions uninhabitable by human and nonhuman. Floods and melting permafrost force migration upon all inhabitants in the arctic¹. Humans and non-humans are engaged in this massive migration together, but conditions are shifting too rapidly for many ecosystems to keep up – an entire forest cannot pull itself out of the ground and move to where the rain has gone. Can migration paths be designed to give humans and ecosystems a chance at success? Can the migration of humans be designed in such a way to create a path for the nonhumans, and vise versa?

Case Study: Cloud Forests

The cloud forests of Central America are currently engaged in an uphill migration, as mountainside temperatures are increasing at a faster rate than lowland temperatures2. Cloud forests are among the most biodiverse regions on Earth, hosting species found nowhere else, widely undiscovered and undocumented by the scientific community. Cloud forests live where the warm, humid trade winds travel up mountain ranges to where the temperature becomes too cold for the wind to hold its moisture. Clouds are formed at this altitude, creating habitats persistently drenched in cool mist. The leaves of plants and trees strip the water from the clouds and cause it to drip into the mossy soil, feeding a multitude of plant and animal species. The water stripped from the clouds then feeds streams and rivers that flow to the valleys, where cities and villages rely on the water. In this way, cloud forests are massive natural water tanks, sustaining human and nonhuman life3.

![Cloud forest near Mindo, Ecuador. Photo by Ayacop (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://expandedenvironment.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/1024px-Mindo-Cloud-Forest-05.jpg)

Cloud forest near Mindo, Ecuador. Photo by Ayacop (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

A warmer atmosphere means that clouds form at higher altitudes, forcing the forests to migrate up the mountains to follow them. For species with legs, such as the spectacled bear or recently discovered olinguito, this may not seem like an issue; but for the plant species that provide water and shelter, the migration is much more difficult. Certain trees in the cloud forest can, indeed, move, as long leg-like roots suspend the trunk from the ground surface, and over the course of years, they can carry the tree several meters over the course of its lifetime4

. Several meters will not keep up with the clouds, which will likely rise over a hundred vertical meters in some cases, and several horizontal kilometers. The hope lies in the next generation, the spreading of seeds and seedlings, carried on the wind and in the digestive tracts of animals.

There are several other factors that are key to the propagation of plant species, such as soil, streams, and groundwater that must move along with the plants and animals. There is a great barrier to these elements – the Puna Grassland in the Andes. The grassland is a massive area where native grasses easily outcompete the cloud forest plants and increased levels of UV make the conditions intolerable for forest species. Additionally, cattle graze on seedlings and many farmers and ranchers burn their fields seasonally5. Some researchers speculate the constructed landslides will help the migration, wiping out the grass species in an area and clearing the way for the forest seedlings. Others are calling for the construction of “semi-transparent screens to create migration corridors,” to decrease the impact of higher solar radiation in the grasslands6. Such approaches, however, call for funding that does not exist and may require a hostile takeover of land from farmers and other people groups.

Should the cloud forests vanish, it is likely that human residents will be displaced as well. The indigenous people sustained by the ecosystems will be without a home, while the villages and cities fed by the watershed will experience water shortage as the clouds soar over the mountaintops, unharvested by trees and mosses. This project seeks to reconnect the movement of humans with the movement of the nonhuman cloud forest. Can human activity assist the migration of the cloud forest, and can the cloud forest inform the migration of humans?

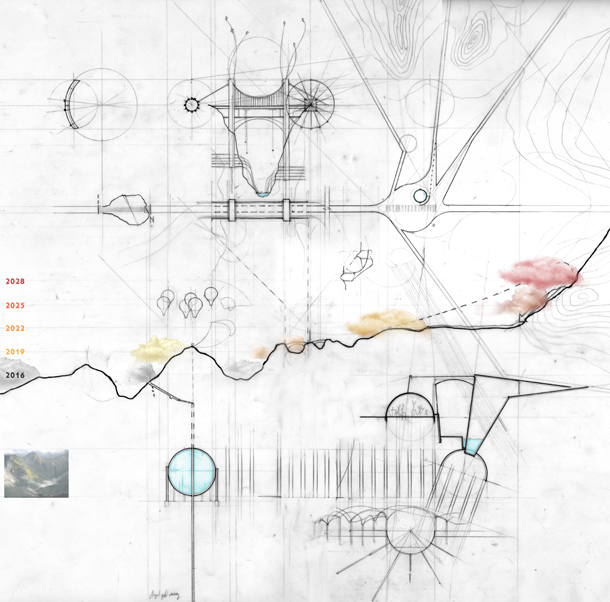

A Design Brainstorm

Indigenous people, with their lifestyles, rituals and traditions deeply rooted in their natural environment, could be expected to follow the same migratory trajectories as the rest of the ecosystem’s species. Because of their integral understanding of how the forests operate, indigenous peoples play a key role in a successful migration. Following examples of cloud forest tribes such as the U’wa people, recognized indigenous territory should be expanded, returning land and preventing further land grabs and resource extraction. The patterns and migrations of the natives must be the basis for non-colonial development of all other migratory routes.

Hikers in the Puna grassland region of Manu National Park. (Photo courtesy of Miles Silman)

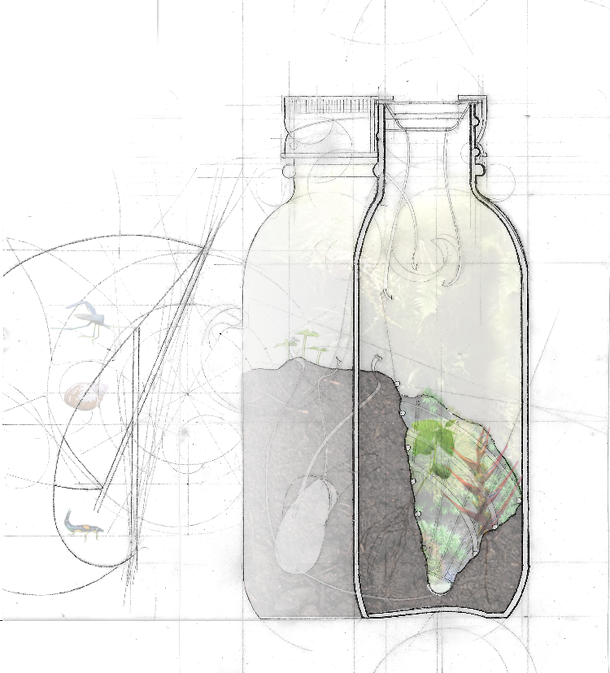

On the opposite side of the spectrum from the native peoples are ecotourists. Tourists visit the cloud forests to sight-see and explore. As a part of receiving permits to enter parts of the forests, this project suggests that tourists must agree to carry with them a cloud forest seedling or plant to be planted at a campsite on the destination side of the grassland. These ecotourists have potential to bring both money and labor to the conservation front by casting them as active participants in the environment, rather than passive consumers of it. Consumption could also play a helpful role in the migration. While commoditization of an ecosystem is one of its greatest threats, turning trees into timber and the other plants and species into overburden to be removed, design can subvert a commodity into a generative force to assist migration. For instance, cloud forests could be “bottled” into engineered terraria for purchase around the world, giving the cloud forest species a selection of habitats to migrate into. For instance, many cloud forest species are found to thrive in the foggy shores of coastal California7. Can commoditization help cloud forests migrate to an entirely different region of earth where all the species could thrive?

Cloud forest terrarium. Commoditization of species might assist in their migration to faraway suitable habitats. (Image by author).

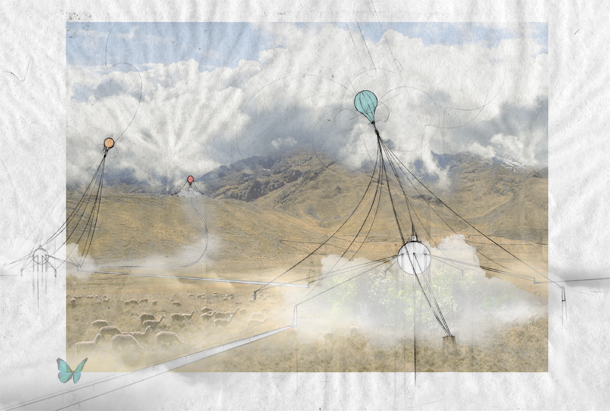

Farmers and ranchers in the Puna require the water for irrigation and the space for their grazing cattle. By designing methods of plowing and irrigating, migration corridors can be created. Irrigation nodes, or “cloud islands”, provide oases for grazing alpaca and destinations for migrating cloud forest species. Plowed canals become “cloud streams” in which smaller species and amphibians can journey towards the islands, which are engineered to be shrouded in mist and thus protected from solar radiation. When the cattle and farmers migrate away, the irrigation nodes decay into forest.

“Cloud Islands” and irrigation channels provide farmers and cattle with water, while serving as destination points for cloud forests. (Image by author).

Mining and logging operations, both legal and illegal, have potential to assist cloud forest migration if designed. A mine is essentially a geothermal chimney, bringing the consistent temperature of the earth to the surface. Mines could help create small microclimatic pockets of cooler air where clouds could form, giving sanctuary to cloud forest species and providing cover for miners hoping to remain unseen. Mining and logging exploration roads can be cut through the puna, to give tree species a chance to compete against the grass species.

Informal, inflatable shelter at entrance to an Andean mine. Clouds form when shelter collects cooler air vacating the mine, combining it with the warmer, humid outside air. Mine entrances become havens for cloud forests, which in turn offer cover and water for miners. (Image by author).

Efforts in designing the migration of an enormous spectrum of human groups and non-human species could prove helpful in sustaining life in a rapidly and unpredictably changing climate. By understanding how humans and non-humans are linked integrally with their environment, methods of comigration begin to reveal themselves, so that displacement or extinction of any species or people group might be minimized. Cloud forests are only one of the thousands of ecosystems endangered by climate change; design analysis of any other environment will produce vastly different concepts.

1 Elizabeth Ferris, “Climate Change is Displacing People Now: Alarmists vs. Skeptics,” Brookings, May 21, 2014, Accessed June 5, 2016, http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/planetpolicy/posts/2014/05/21-climate-change-displacement-ferris.

2 Jeremy Hance, “Climate change could kill off Andean cloud forests, home to thousands of species found nowhere else,” Mongabay, September 18, 2013, Accessed May 16, 2016, https://news.mongabay.com/2013/09/climate-change-could-kill-off-andean-cloud-forests-home-to-thousands-of-species-found-nowhere-else.

3 “Cloud Forest Conservation,” http://www.cloudforestconservation.org/cloud_forest.

4 Karin-Marijke Vis, “The Amazing Flora and Fauna of Cloud Forests,” Matador Network, December 7, 2014.

5 Hance, “Climate change could kill off Andean cloud forests.”

6 Hance, “Climate change could kill off Andean cloud forests.”

7 “Cloud Forests,” San Francisco Botanical Garden, http://www.sfbotanicalgarden.org/cf/cf.