The screening wall at Hrishikesh Laha’s residence on Amherst Street, Kolkata. Photo: Amartya Deb, 16 July 2018.

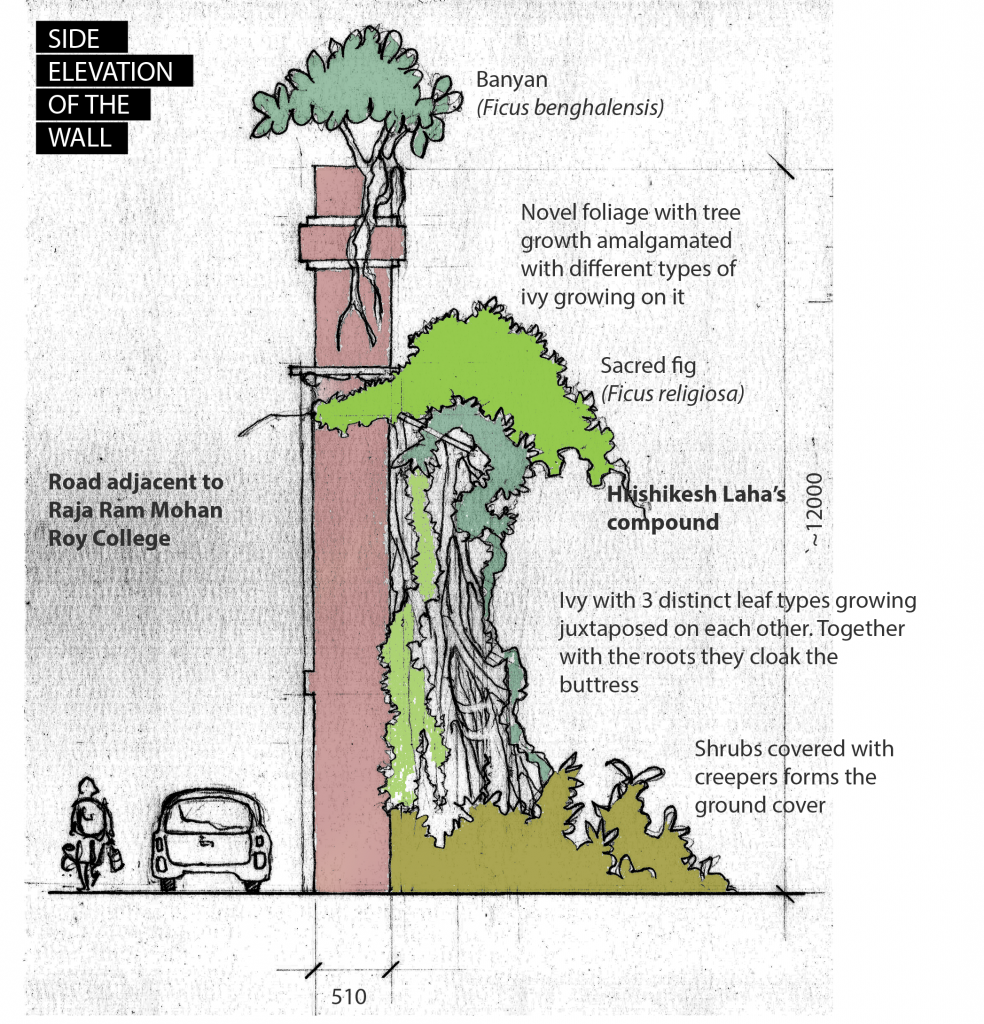

There is a giant wall standing erect at the edge of Hrishikesh Laha’s residential compound on Amherst Street. I am not sure if I would have noticed it, had it not been for the tree growth that has created a fantastic sculpture around one of its buttresses. Of course, the wall is not only beautiful in its structural components like arches and buttresses, but also in its colonial feel of size, grandeur and ornamentation carved on it. Two different species of trees and three species of ivy can be identified growing on it – made distinct due to their leaf structure and the varied shades of green (see illustration below). All the growth incidentally focuses on one corner of the wall, making it rich in biological diversity and density. Together with the natural and man-made elements, the wall becomes an artistic precinct that begs investigation towards both an explanation and purpose for its aesthetics.

An iconoclastic precinct of colonial architecture

As an architect, I should have been intrigued by the wonderfully crafted structure even without the biological growth. But it so happens that in formerly-colonial parts of Calcutta (now Kolkata), such beautiful precincts of architecture are rather too common. They are so dense that every now and then, one hears an old building getting knocked down to make way for the new; and still many remain. In fact, my first impression of the wall was that it too must be a remaining bit of a demolished building that existed before. But looking at the wall more closely, one can observe the buttresses supporting it from collapsing inwards. With the ornamental motifs facing the Laha residence and not the road, clearly, this is a façade intended to be viewed from inside the compound.

Ronjon Sircar who has been security personnel for about eight years on the site shared that the wall, as heard, was erected to preserve the privacy of the residents from the neighbouring college. Given the residence of Hrishikesh Laha was built during the early 1900s and the Rammohan College (or City College) was established in 1880s, this wall can potentially date back to a century ago. Since the massive boundary-wall was erected as only a visual barrier; the remaining walls of the compound are not only low height but also lack any sort of measures like nails or spears prevalent at the time for stopping human entry. It was thrilling to know that the post-material value of privacy was so much of a concern for the businessman of Calcutta – that a wall measuring as high as 12 metres (36 feet) in height was erected. Today, with a growing population density of the city, the wall then becomes a relevant monument that helps understand the importance of non-intrusion in peoples’ lives.

Biological growth adding value to the historical precinct

The wall, of course, has an aforementioned social value that is attached to its historicity. However, today the formerly residential building is appropriated to accommodate a news company; diluting the visual privacy concerns. A wide vacant yard before the wall still exists that has made way for wild growth. It is certain that the wall no longer serves as a screen. Yet, the art value of the co-created landscape cannot be ignored. The biological growth elevates the value of the wall into that of a unique sculpture. On one hand, the wall would be boring without the biological growth: the growing trees adds in terms of real floral and organic patterns to an otherwise ‘regular’ wall of the colonial era. On the other hand, a section of the wall is continuously subjected to root-action of trees. Mr Sircar revealed how every two years, the sacred fig (also known as Peepal tree) growing on the buttress is pruned – but only for it to grow back. I was surprised to learn that the growth which otherwise looked so natural was actually managed; albeit with no real intention of letting the plants grow back. This informal interaction to otherwise safeguard the architectural feature is responsible for increasing the lifespan of the co-created landscape by nature and human.

Side elevation of the wall at Amherst Street. Illustration by author for Expanded Environment.

Side elevation of the wall at Amherst Street. Illustration by author for Expanded Environment.

As geographer and urbanist Matthew Gandy suggests, unintentional landscapes (pdf) isn’t just wild growth, but one that has gone through some sort of “sensory enframement” to appear aesthetic. In this case, I find the sensory aspects to be freshness added by the growth of trees; and shades of green due to different species that pronounce each living floral element. The growth of trees and ivy are far easily spotted than micro growth such as moss on the wall which needs closer inspection. The ‘visual directness’ of wild growth adds focal point to an otherwise boring image of the wall. The contrast offered through complementary colours – red bricks and green leaves – allow the audience to distinguish between, and appreciate, both the man-made as well as the natural elements of our co-created sculpture. Finally, the tint of light blue on the lower half of the wall acts neutral; yet adding to the drama by highlighting the dark clouds in the otherwise blue sky. This creates a continuum between the ‘canvas’ and the subjects.

The growth which otherwise looked so natural was actually managed; albeit with no real intention of letting the plants grow back. This informal interaction to otherwise safeguard the architectural feature is responsible for increasing the lifespan of the co-created landscape by nature and human.

Retain co-created sculpture for better storytelling

The case of Hrishikesh Laha’s residence is an example of how natural growth on buildings can play a powerful role in storytelling. In Hong Kong, Chinese banyan trees growing out of masonry walls have won the acceptance of the residents due to their interesting shapes and collective memory values; memories from even before the World War II. Bearing in mind, an intensive study (pdf) done on the city’s 1275 stone-wall trees recommends routine inspection and appropriate structural precautions to retain such unique nature of landscape within the city. To return to our case on Amherst Street, Calcutta –only a small part of the wall is subject to the tree action. The plants are growing in one corner as opposed to growing all over the massive extent of the wall. Also, fortunately, the growth does not conceal relevant architectural features of the wall. I would hope that with professional management this novel setting can be retained in its present beauty. Having a high art-value, the natural growth accompanies the storytelling of late Hrishikesh Laha (1852-1935) with a more visually pleasing experience. Then I find my learning rather straightforward i.e. to preserve the story, preserve the wall. But to tell the story, keep the growth.