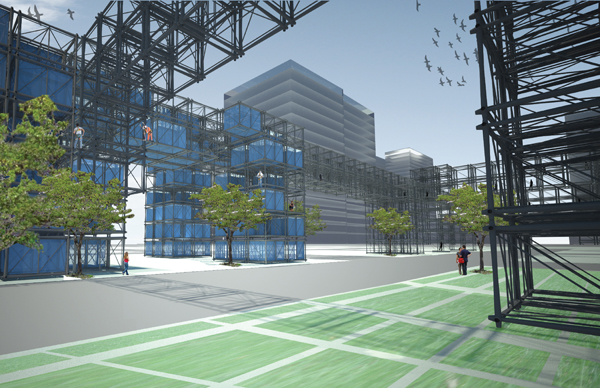

The Scaffolding City, perspective view.

*This article is scheduled for publication in the up-coming issue of Bracket – [goes soft] and is currently available for pre-order at amazon.com.

IN SEARCH OF A SEMI-LIVING ARCHITECTURE

Edward Dodington

We have lost touch with the softer systems of dynamic change that live within and around us — systems that govern our very existence. In an expanding and increasingly volatile world an anachronistic model of architecture and urbanism based on planning, authority, history and permanence has less and less ability to solve today’s economic and ecological problems. Instead, a system of speed, flexibility and soft-structure is required for the World’s most complex social, environmental, and economic issues.

This is not the first time that an architectural solution of speed, lightness and flexibility has been proposed to solve our most challenging urban problems. Avant-garde thinkers in the mid 1950’s and ‘60’s in Europe and America such as Cedric Price, Buckminster Fuller, Peter Cook and particularly Yona Friedman proposed radically flexible and mobile models of architecture and urbanism to solve some of the most pressing and visible problems of the immediately post-war world (1). Yet there was something missing, aberrant, or unsettling about each mega-structuralist project (fictitious, totalitarian, too widely accepted…). In many ways the mega-structural projects (in their form of proposals) did not fully realize their promises of freedom and democracy. They sought to upend social and economic hierarchies in the world through architectural design, restructure academies, and democratize the construction process only to find themselves on the cover of design magazines, lecturing in the same schools and, at the end of the process, still left with an architectural artifact. After much praise and optimism the project as a whole was abandoned. By the 1970’s Banham, previously a vocal champion of the project declared the “megastructure is Dead (2) ” A new generation of architects took its place and focused on a smaller scale of modular architectural proposals – with their own set of potentials and limits (3). But now, perhaps our world has returned to that period of time when thinking bigger was thinking better…

Illustration of a housing unit in the Scaffolding City.

In the late 1950’s Friedman theorized a “Mobile Architecture.” His Spatial City of 1958 (figs. 1 and 2), the manifestation of this theory, demonstrates this mobility by establishing a three dimensional space-frame over a zone (city, farm, highway) providing an infinitely flexible space for the inhabitants.

It is time to revive the Megastructuralists. Urban scenarios with aspirations to infinite flexibility, quickness of construction, lightness of materials and “plug and play” techniques borrowed from Fuller and Freidman are needed again. But this time they must be wedded to an equal vision of past building methods (tents, wigwams, tee-pees, and stick-structures) and a greater understanding of even larger ecological and biological models of growth and development. The Scaffolding City draws upon aspects of three disparate though related worlds, creating something of a motley synthesis — that of the Megastructure, the indigenous architecture, and the biological — to posit a new version of living in an old way.

Image used with the permission of the Starn Brothers, Copyright, D+M Starn, 2011.

The Starn Brothers, Doug and Mike, in the last few years have constructed massive flexible bamboo structures for artistic exploration and temporary occupation (visitors are invited to walk in among the works). Two works, Big Bambu and Big Bambu You can’t You wont and You don’t Stop, are intricate, sometimes delicate, scaffolding-like structures constructed in a traditional method with long bamboo rods. The scope of the structures are generally planned but the majority of the construction work and execution remains ad-hoc, with teams of volunteers climbing, tying and binding the rods together more or less autonomously. The structures are never fully complete and instead exist in a state of constant change and motion. Not only is there a kind of perpetual cycle of construction occurring on the works but the elastic properties of bamboo allow for a gentle movement and flow throughout the structure. Most interestingly and valuably is the infinite flexibility of the mechanical parts in the system. Such a system allows each piece a remarkable degree of flexibility within the system – it can be moved, used and reused in multiple locations (and often is). In this system loads are distributed over a huge array of members with the understanding that micro-structural failures might occur in specific locations but a large scale failure is unlikely. The method of construction (lashing branches) used by the Starn brothers is locally simple and globally complex — specific, simple and basic construction techniques resulting in a complex and dynamic global arrangement and while not typically characterized as an “efficient system” it is defined by the new three “R’s” — redundancy, repetition and resiliency.

A scaffolding town-house (Dodington) and the work of the Starn Brothers. This new urban systems of habitation will rely on the successful integration and synthesis of several hard and soft systems. Image used with the permission of the Starn Brothers, Copyright, D+M Starn, 2011.

Illustration of a housing unit in the Scaffolding City.

This type of locally specific / globally complex system can be seen in a variety of other biological systems at an equally diverse range of scales – most poignantly in the formation and growth of calcium deposits in bone structures. As a system, the skeleton fulfills the “scaffolding, armoring, and damping functions necessary for survival of mobile terrestrial organisms (4)” and is a constantly fluctuating supply of calcium for the body. However, at the microscopic scale bone is brittle and not particularly strong, often suffering many micro-fractures on a routine basis. The strength and flexibility of the system is due in part to a very heterogeneous composition. Your average bone is a complex matrix of calcified members creating a rigid sponge with a corresponding system of lacunocanalicular and intraosseous (marrow and blood) fluid networks. This fluid system is responsible for two main roles – the reabsorption and extraction of calcium and other minerals in the bone, and regulating morphology. The intraosseous fluid is composed of osteoblasts and their number, shape and health influence bone morphology, the larger implication here though is that bone, rather than being a static, rigid homogenous material is a constantly changing expression of “endogenous and exogenous mechanobiological signals,” in short a map of internal and external forces.

Detail of a typical lashed connection in Big Bambu; You Can’t, You Won’t and You Don’t Stop constructed in the fall of 2010 on the Roof of The MET in NYC. Copyright, D+M Starn, 2011. Right: Detail of typical commercially available scaffolding system, this one, in particular is employed at the Authors apartment complex in Houston Texas.

In a similar vein the scaffolding city would develop an architectural system that responds quickly and flexibly to the internal and external pressures – be they urban, economic, or ecological. And as such it cannot exist on its own. The scaffolding city, as the intraosseous fluid in our bones, must rely upon and work with our more solid urban structures. Faced with these scenarios it becomes a second complimentary system of urban habitation – a system of disaster-preparedness – of thickening urban edges – of redundant habitation and easily accessible construction materials.

Much like the work of those avant-garde architects nearly 50 years ago, the scaffolding city attempts to re-position architecture as a flexible strategy of urban habitation, and not as a prescriptive solution to an unknowable problem. Yet unlike many of theorized projects of those same avant- gardists it will come to more closely resemble a type of semi-living system characterized by real-time change and adaptability found in flexible construction techniques in Sri-Lanka, India, and other largely tropical parts of the world, or to the system of material transfer deep within the lacunocanalicular network.

Scaffolding City is a place where citizens hold the potential to reshape their cities and where the built landscape becomes a collectively more active, agile and soft system. It is a radically heterogeneous city — part super-structure, part favela, part bird-nest and part tree house where many different urban animals can roost, camp, and live. It is sometimes a parasitic or a symbiotic structure, latching on to other structures or borrowing resources for a short amount of time. In return, Scaffolding City capitalizes under-utilized spaces and generates micro-economies of alternative resources. This city has never been seen before but might look strangely familiar. It is a city from the future past.

Scaffolding City Perspective Flyover

Principles:

The Need for Speed

Our current model of architecture is too slow. It is too slow to respond to global ecological and economic crisis alike. We need a faster system. One that can quickly adapt, bend, strategically buckle, and rebuild. The trend has been moving in the direction of increasing speed — it just needs to get faster.

Redundancy

The new ethos is for designers to embrace change and flexibility — unknowns will remain unknown and new unknowns will be discovered. To design for eventual and partial failure is more realistic than an “impervious” or materially efficient design.

Network the System

The development plan of the city will rely not on a strict plan but on access and proximity to resources, local economic conditions and ecology. This will be a dynamic system of planning, free to move from location to location.

Open to Economy

Incentivize use. Keep material costs low and the system will generate innovative uses and techniques. People will re-interpret materials, re-invent uses and develop secondary and tertiary economies surrounding the transfer and transformation of materials.

Democratize the Construction Process

and lower the level of specialized construction knowledge. Each citizen can become a contractor, and thereby become an active member of a growing system.

Open to Ecology

The new architectural city will be easily accessible and amenable to other animals for civic habitation. Its openness will take advantage of ecological assets, getting stronger as it is incorporated into a living thicket of trees or gathering thicker as populations of birds and animals make it their homes.

Notes and References:

1) In the late 1950’s Friedman theorized a “Mobile Architecture.” His Spatial City of 1958 (figs. 1 and 2), the manifestation of this theory, demonstrates this mobility by establishing a three dimensional space-frame over a zone (city, farm, highway) providing an infinitely flexible space for the inhabitants.

2) “Banham, La Megastructure e morta,” Casabella 375 (1973), p. 2 quoted in Megastructure Reloaded; van der Levy and Richter, Hatje Cantz Verlag, p. 28.

3) Sabrina van der Levy, Markus Richter, Megastructure Reloaded, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern; Berlin 2008, 29-31.

4) Tate, Melissa L. Knothe, “Wither flows the fluid in bone?” Published in the Journal of Biomechanics. Volume 36, Issue 10, October 2003, pages 1409-1424.

5) This essay was written By Edward (Ned) Dodington and is scheduled for publication in the Second issue of Bracket (BRKT) titled “Goes Soft” to appear in print later this year.

Image Captions and Credits:

1 (Tower Group). The Scaffolding City, perspective view.

2. A scaffolding town-house and the work of the Starn Brothers. This new urban systems of habitation will rely on the successful integration and synthesis of several hard and soft systems. Image used with the permission of the Starn Brothers, Copyright, D+M Starn, 2011.

3. Detail of a typical lashed connection in Big Bambu; You Can’t, You Won’t and You Don’t Stop constructed in the fall of 2010 on the Roof of The MET in NYC. Copyright, D+M Starn, 2011. Right: Detail of typical commercially available scaffolding system, this one, in particular is employed at the Authors apartment complex in Houston Texas.

4. Illustration of a housing unit in the Scaffolding City.

5. Multiple structural, enclosure, and utility systems must be utilized simultaneously and easily within the new system, as opposed to a singular mono-logical use.

6. The Scaffolding City as tower and clip-on structure. The Scaffolding city will have to rely on “tapping-into” and “plugging-into” existing utility sources to meet the needs of its inhabitants. In these scenarios it will function as a symbiotic parasite, adding additional use, structure and maintenance to an existing structure, for access to water, power and waste systems.

7. Scaffolding City Perspective Section and Aerial.

8. Scaffolding City Perspective Flyover.

9. “…locally specific / globally complex system can be seen in a variety of other biological systems at an equally diverse range of scales…” Big Bambu Image: Copyright, D+M Starn, 2011.

10. The Need for Speed; a story in Three Diagrams (Old, Current and Future). Our current model of architecture is too slow. It is too slow to respond to global ecological and economic crisis alike. We need a faster system. One that can quickly adapt, bend, strategically buckle, and rebuild. The trend has been moving in the direction of increasing speed — it just needs to get faster.

11. All images and content unless otherwise indicated are copyright Edward (Ned) Dodington.

1 comment

Comments are closed.