Decompositions : Introduction

As the human habitat expands to cover the earth it replaces, dissects and pollutes habitats of non-humans, driving them to potential extinction. To preserve non-humans on earth our built habitats must evolve (decompose) to be inclusive of nonhuman species. There are many reasons to do this. Many are rooted in sustainability, others in pragmatism, and some in empathy.

The following projects offer another reason for sharing our spaces with non-human species: the enrichment of our spaces and our own perception. Animals, with their myriad superhuman senses, can teach us new unprecedented ways of occupying space. Shared spaces can allow us to mentally occupy each other, sensing our spaces with new eyes, new ears, new antennae, new tentacles. All species benefit from the sharing of space.

The following projects suggest a decomposed architecture – where the human and the animal share spaces, seasonal rituals, methods of migration, senses and superpowers. They begin to suggest ways that humans can invite animals into their spaces to mutually enhance the spaces and the ways of living in them.

Decompositions I : Forest [Hunting Outpost]

How can sharing spaces lead us to a deeper understanding of our space? Can we learn the senses of other species? Can we gain an animal’s superpowers?

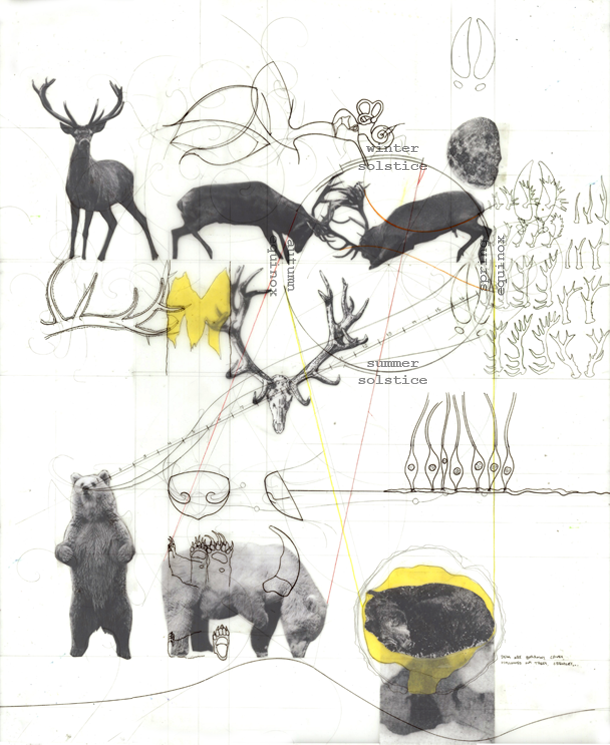

A bear can occupy space with her nose. Many species of bear can catch a scent over 17 miles away that hasn’t been there in days – they can smell across space and time. This ability makes the bear a great hunter, in addition to her sharp claws and teeth, speed, and size. The bear must be a good hunter, because winter is always approaching. Over winter, bears demonstrate another unique way of occupying space: hibernation. Entering a state that can be described as neither consciousness nor unconsciousness, the bear reduces her breathing, body temperature, heart rate and metabolic rate and burrows in a den, tree hollow or cave. A mother gives birth during this time, with months remaining until the thaw. The bear reemerges in spring and begins the hunt again. What strange spatial realms does the bear experience during this dormancy?

The stag can occupy space with his sense of hearing. Directional ears rotate towards a sound, amplifying it through highly evolved ear canals. A Stag, like the bear, also has a biological method of occupying time: the growth of antlers. A stag grows and sheds a new set of antlers every year, each regrowth larger and more articulated than the lost. The antlers are used in the autumn mating ritual to spar with other stags, which fills the forest with orchestras of clattering bone. The sounds draw more competitors, mates, as well as potential predators.

Can humans gain such superpowers by sharing spaces with these animals? Can the animals also benefit from human design, gaining new tools for their hunt and their rituals?

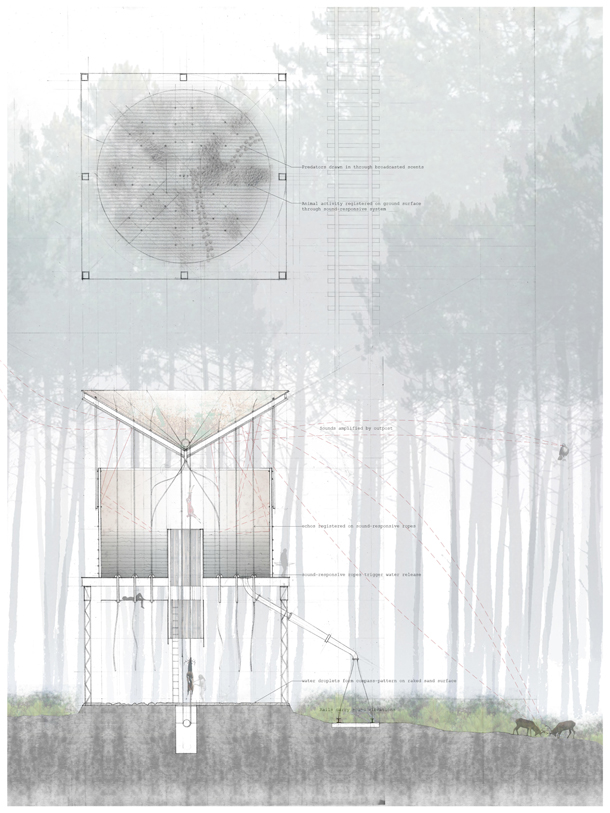

The above image suggests a cohabited design. In the forest habitat, migrants and predators aid each other in locating prey. Old water tanks are transformed into pan-species hunting outposts. These outposts amplify sounds of activity in the forest – stags calling and sparring, bears moving and hunting, and the plethora of other animals in the forest. The sounds are transferred through sound-responsive ropes that release water onto the raked sand ground surface, creating a compass pattern pointing toward the areas with the most activity. Humans use these compass patterns to locate prey and return it to the outpost, which broadcasts scents into the surrounding forest. Predators and more animals are drawn toward these scents, creating a web of overlapping species and shared spaces. Humans and non-humans assist each other in locating mutual prey through broadcast scents and sounds. The architecture creates a library of superpowers to be shared by all species in the vicinity.