Continued from The Architectural Animal: Part 3

MONSTROUS LANDSCAPES

“Landscape” is, again like the terms “monster” and “animal” that we have seen previously, a word that dramatically oversimplifies an unimaginably complex system. When one typically thinks of Landscape, more than likely we all, form a fairly predicable mental description. To be frank, we are usually talking about images of the horizontal surface upon which we walk. Landscape Architects and designers, make it their mission to “order”, “improve” and otherwise control this plane. They employ tools such as earth-moving, paving, and strategic planting towards the end of creating marketable environments and spaces for human enjoyment. This often means that the landscape is stripped of many otherwise integral characteristics. Bugs, fungus, bacteria, and microscopic organisms, though never completely removed are unwanted if not severely curtailed, not to mention the very typical and important processes of decay and death. These practices demonstrate a narrowing of the complexities of landscape to fit an already prescribed image of what landscape should be. This amounts to an analogous kind of species-ism that Derrida, Haraway and others have rallied against in their collective published works against “the Animal” and “the Other.” Just as Derrida and Haraway argue for a posthumanist philosophy of animality I would ask now “how do we achieve a posthumanity in our built (and unbuilt) environments?” How do we, now understanding the complexities of our condition with our companion species, live?

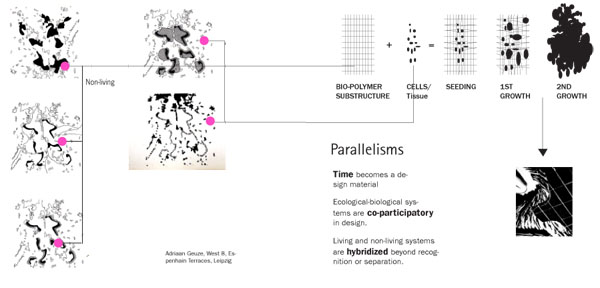

It has only been within the last decade and certainly within the last generation of designers that the complexity of life in a given landscape have begun to receive due credit. The emerging discipline of Landscape Urbanism, pioneered by Charles Waldheim, James Corner and a small group of predominately architects and urban planners, is developing a significant body of discourse and experimental projects driven towards a new understanding of what a post-humanist environment might mean. Collectively they are developing the most current definition of landscape and urbanism and consequently new methods to avoid the fictions we found in “Animal.” Just as a posthumanist, or non-humanist definition of “animal” demands an expanded philosophical and moral attitude towards our myriad messmates a theory or ethic towards Landscape and Urbanism requires a redefinition; something close to what James Corner has so aptly termed Terra Fluxus.

“In conceptualizing a more organic, fluid urbanism, ecology itself becomes an extremely useful lens through which to analyze and project alternative urban futures…thus, dynamic relationships and agencies of process become highlighted in ecological thinking, accounting for a particular spatial form as merely provisional state of matter, on its way to becoming something else.”

And further:

“This work must necessarily view the entire metropolis as a living arena of processes and exchanges over time, allowing new forces and relationships to prepare the ground for new activities and patterns of occupancy. The designation Terra Firma (firm, not changing; fixed and definite) gives way in favor of the shifting processes coursing through and across the urban field: terra fluxus.”

The static plane of sod, turf and choice ecologies has been replaced by an ever shifting flow of energies across a biased plane. Clearly this is not the landscape of “the animal” (note the definitive article) but of animals in the most plural sense. Similarly the city has changed as well. The definition has moved from the living organism of Berger’s essay to the living arena of processes. Corner’s city is not a singular animal, even if it is composed of many different entities. It is a constantly changing milieu.

Christopher Hight in his essay “Portraying the Urban Landscape: Landscape in Architectural Criticism and Theory, 1960-Present” takes a slightly different approach. In this essay he suggests an even more dispersed image of the landscape than Corner and stresses the violent potential of landscape to undermine the history of Architectural production.

“…the horizontal landscape is the mode of all of their processes of anti-oedipalization: the “body without organs’, the becoming animal’, the becoming rhizome, nomadology, the war machine.”

However, though pregnant with post-humanist or anti-humanist potential, Hight reminds us that Landscape Urbanism does not offer a clear formal response to the problematic anthropomorphism of architecture. Landscape Urbanism is not so much applicable as a design strategy or particularly useful in looking at the landscape itself but instead offers a “design ethic.”

“In this way, Landscape Urbanism offers, to use an unfashionable and misunderstood term, a design ethic. By this I do not mean a moral code, a legal standard or a ‘green’ mantra. Instead I refer to ethos: a way of doing and a mentality which privileges certain values, norms, assumptions and methods, and which treats particular problems in particular ways.”

Here Hight turns to the Foucaultian theory of the disassembled self and Deleuze and Guattari’s body without organs. For Hight, both the disassembled body and the body without organs reflect a “freeing, distancing or more precisely, [a] disassembling of the essentialist humanist subject.” Landscape Urbanism, as Hight is careful to make clear, does not attempt to show us how to interact with what we call landscape or urbanism but…

“disassembles the identity of the architect and the urbanist and opens their fields of knowledge to ‘other’ potentials. Landscape urbanism, if it is to be anything must be understood as an attempt ‘to constitute a kind of ethics [as] an aesthetics of existence.”

It would appear that, like two positively charged magnets, the forced combination of the polar terms “Landscape” and “Urbanism” has resulted in a kind of dramatic othering of both, and an attempt to reconceptualize each. The ethics of landscape, as Hight would have us believe, is localized around a dispersed body, and with that we can now see a given ecosystem as analogous to Haraway’s symphony of companion species. Let me remind you of Haraway’s companion species:

“Organisms are ecosystems of genomes, consortia, communities, partly digested dinners, mortal boundary formations. Even toy dogs and fat old ladies on city streets are such boundary formations; studying them ‘ecologically’ would show it.”

Isn’t it odd that Haraway talks of studying bodies ecologically while Hight and other landscape urbanists look at ecology as if it were bodies? Under such terms it becomes difficult to see a difference between a body and an ecosystem. But while Haraway and Derrida can point to the physical, actual others that commingle in our bodies (bacteria, protists and cats respectively) what are Hight’s bodies, or fragments of the previous body? Judging from the works of current Landscape Urbanists they are the visible and invisible systems that operate in and around landscape. They are not the living organisms, but their independent and combined processes of existence. As such it becomes difficult to guess what Haraway would suggest if one were to be, to use her words “polite” and “respectful” of our poly-species companions if in fact they are not so much living entities but systems and flows of energy. It becomes even more complex when one recognizes oneself as part of the system at hand, thus to be “polite” would be being polite to oneself. And if we take this leap, what are there rules of engagement?

At the end of the first chapter of “When Species Meet” Donna Hararway offers little practical guidance for living a more polite life.

“Once again we are in a knot of species co-shaping one another in layers of reciprocating complexity all the way down. Response and respect are possible only in those knots, with actual animals and people looking back at each other, sticky with all their muddled histories…It is a question of learning to be ‘polite’ in responsible relation to always asymmetrical living and dying, and nurturing and killing. And so I end with the alpine tourist brochure’s severe injunction to the hiker to “be on your best countryside behavior.”

And it is here that the Landscape Urbanist should step in and say “Wait! There are physical ways to be more polite.” Just as there are table manners, and social guides of decorum there are, should or can be, ways of formally interacting with this thing called landscape that would ensure mutual responsibility. Ultimately this is where Landscape Urbanism needs to be. Hight stressed that the landscape urbanism ethic does not include a moral imperative and I say, why not? If landscape is indeed composed of these multiple and complex ecologies why not respect them and give them the responsibility they deserve? As Derrida would say “to have the plural of animals heard in the singular.” But how? Surely you can’t hear the plurality if you don’t know how to listen. And you cannot be polite if you don’t know the customs. How does one enter into the social constraints of the landscape, of ecology? More frighteningly, are we ever not already seated at the table?

I bring us back to the animal and the monster, and what we had previously determined were actually two monsters. What does a monster de-monstrate? How does one “other” see or understand what is being shown by another other? Only then, once we have heard, can we ask how to respond.

to be continued…