Portions of this article originally appeared in the 2013 ACSA conference Proceedings “New Constellations/New Ecologies”.

Since its founding in 2009 Animal Architecture has amassed a over 200 distinct projects coalescing into a significant body of work. While there are many different projects on the website in general three basic groups of projects can be discerned: Synanthropic Habitats, Soft Structures and Post-Animal Alternate Realities with Synanthropic Habitats being the most numerous by far. We’ve decided in this next series to take a step back and engage in a little introspection. What does the work on Animal Architecture indicate about the status of the still nascent field? What does it say about us as Humans and specifically as agents in a complex world? The next several stories will expand upon some earlier ideas and attempt to give a reading on the pulse of the Animal Architecture movement five years from inception.

Bat Cloud: Joyce Hwang, Sze Wan Li, Mikaila Waters, Robert Yoos, Molly Hogle, Duane Warren, Shawn Lewis, Mark Bajorek, Katharina Dittmar, Matthieu Bain, Joshua Gardner, Shawn Lewis, Sergio López-Piñeiro, Nellie Niespodzinski, Mark Nowaczyk, Alex Poklinkowski, Joseph Swerdlin, Duane Warren, Robert Yoos, Colleen Culleton, Justin Read of the UB Humanities Institute, and Lauren Makeyenko and David Spiering of Tifft Nature Preserve for facilitating the project’s installation.

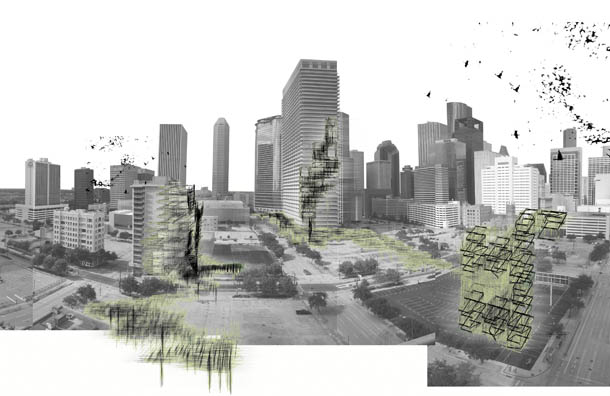

Synanthropic Habitats propose scenarios where animals and humans live closely together in cross-species cities or abodes – they are the projects that most often come to mind when one thinks of Animal Architecture. Synanthropic Habitats are Bird Scrapers, Hive Cities, Feral Cities, Pest Walls, OysterTectures, Animal Estates, and The Truffle among many many others (images below. Please click on links to read more about each project). In general they suggest a shared design scenario whereby both the human and animal inhabitants, be they bats, oysters, or birds share in a kind of urban, occasionally residential co-habitation. They are the most numerous design proposals on Animal Architecture and are perhaps best exemplified by the 2012 winning Animal Architecture Award project, Bat Cloud by Joyce Hwang (pictured below).

The basic modis-operandi of Synanthropic Habitats is humans making concerted efforts to design for, improve, and invite alternate species into human environments.

These projects, like Joyce Hwang’s Hive City, or Bat Cloud often rely on a system of attraction or repulsion to help incentivize animal life to occur in particular locations which have been predetermined to be beneficial or at least not detrimental to human habitation, and of course beneficial to the animal inhabitant. Synanthropic projects also tend to involve a hefty amount of prescriptive design for the animal in question. The suggestion is that human design-efforts can indeed improve upon their otherwise naturally occurring habitations (for example assuming that bees would rather live in a built hive, or that birds would rather live in a designed house than their normal residential options). Occasionally the projects add a layer of positive human attributes like alternative energy production, protection from rising sea-levels, or increased pest control. Projects such as Kate Orff’s Oystertecture or Z. Huang’s Bird Scraper demonstrate these kinds of positive design strategies where the particularities of the non-human habitation promises a benefit for the humans.

Hive City Design Team: Courtney Creenan, Lisa Stern, Kyle Mastalinski, Daniel Nead, Scott Selin; Competition Organized by Joyce Hwang, Martha Bohm, Chris Romano and the Ecological Practices Research Group in the SUNY Buffalo Architecture Department.

Oyster-Tecture: Kate Orff, ScapeStudio

BirdScraper by Zhong Huang

Over-all the Synanthropic Habitats strike a kind of ambivalent posture with respect to design. Inevitably there comes a point where a lack of biological information will ultimately challenge the basic assumption that a designed habitat will be more suitable than the “natural habitat” to the chosen animal. Unlike a human client the alien tastes of the animal-client poses a major design problem for an otherwise standard design project. The reality is that in most cases biologists have very little idea what the size, shape, arrangement or color of materials will be more or less suitable for a given animal. So, the projects are then often over-designed and aestheticised or under-designed knowing that there is a very real chance that despite all of the best intentions, the animals simply will not come. Or more likely that whether they do or do not arrive will depend on an entirely other set of factors such as proximity to water, food, or protection from predators.

Bat Station by Friend and Company Architects

Synanthropic projects rely on a collaborative relationship between human and animal partners and this is not unique to them alone – indeed most, if not all, of the projects on Animal Architecture claim some-kind of symbiotic relationship and propose a kind of utopian other-world view that is possibly slightly romanticised, and usually optimistic. This utopian world-view might be best described by what Donna Haraway has termed an autre-mondialisation or “liveable other world[i]” made possible through poly-species alchemy where 1+1 = an unknown and potentially unimaginable reality. Of course there is a risk to this co-species alchemy. That risk is our own humanity. As Haraway suggests, in such projects there is “no teleological warrant here, no assured happy or unhappy ending, socially, ecologically, or scientifically. There is only that chance for getting on together with some grace.[ii]” But the potential benefits are enormous. More than simply benefiting from an increasing number of companion species, is the opportunity to “cross the great divides[iii]“.

In such projects, Synanthropic Habitats and other Animal Architecture projects in general, lies the potential to “flatten into mundane differences” the animal/human, nature/culture and organic/technical divides that have served to under-pin the majority of western culture – including the history of architecture.

While it’s difficult at this time to claim that any synanthropic habitat has flattened the human/animal divide, it is however, fair to claim that with time such projects hold the potential to radically redefine architecture and design. Moreover such projects are certainly, at this moment, changing popular opinion about animal agency in design practices.

-ND