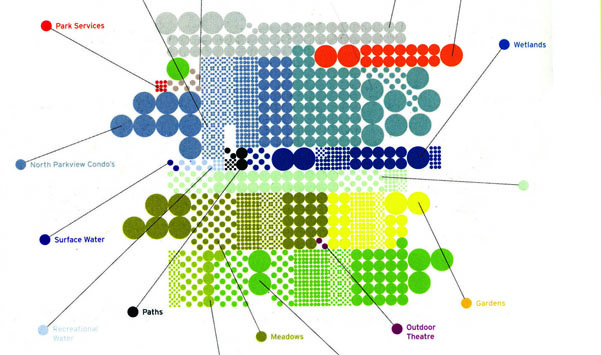

OMA, Downsview Park Drawing

Continued from part 1.

“A Monstrous Architecture,” is a serialized collaboration between Ryan Ludwig (previous contributor to Animal Architecture and Assistant Professor of Architecture at Syracuse University) and Ned Dodington. In 2011-2012 Ryan and Ned had collaborated on a series of posts titled Architecture in the Darwinian Arena. The postings and conversations that arose from this series resulted in a longer discussion about the over-arching role of biology in Architecture and Design; specifically how designers were using biology, either literally, metaphorically, or symbolically in their works. The resulting publication is an attempt to unpack the ethical and metaphysical implications of engaging non-human and environmental factors in design.

Co-authored by

Ned Dodington and Ryan Ludwig

Monstrosity is made manifest in various ways across the discipline of Architecture. This is the third and final installment of a joint editorial project on the topic of Monstrosity in architecture and design. We pick up where the last installment ended describing several types of Monstrous Architectures; previously we had discussed the Hopeful Monster and now we continue with Frankesteins, Imposters and Aliens.

COLLAGE: Frankenstein is a collage — a disparate and uncanny amalgamation of unique parts, some living and some artificial. The emerging discipline of Landscape Urbanism, pioneered by Charles Waldheim, James Corner and a small group of predominately architects and urban planners, is developing a significant body of discourse and experimental projects driven towards a new understanding of what a Monstrous environment might mean — something that James Corner has termed Terra Fluxus. In conceptualizing a more organic, fluid urbanism, ecology itself becomes an extremely useful lens through which to analyze and project alternative urban futures and the world becomes a collage:

…thus, dynamic relationships and agencies of process become highlighted in ecological thinking, accounting for a particular spatial form as merely provisional state of matter, on its way to becoming something else.”

And further: “This work must necessarily view the entire metropolis as a living arena of processes and exchanges over time, allowing new forces and relationships to prepare the ground for new activities and patterns of occupancy. The designation Terra Firma (firm, not changing; fixed and definite) gives way in favor of the shifting processes coursing through and across the urban field: terra fluxus. The static plane of sod, turf and choice ecologies has been replaced by an ever shifting flow of energies across a biased plane.

For the Landscape Urbanists living and non-living things are merely bits of energy in the flow of time. It is a constantly changing milieu. This can be a very powerful frankestienian attitude towards monstrosity where not only is the speciesism of architecture under-cut by life itself, but now animate and inanimate entities are treated equally as forces merely associated with time in an interconnected web, or as corner says “across a biased plane.”

Christopher Hight carries this idea one step further in his essay “Portraying the Urban Landscape: Landscape in Architectural Criticism and Theory, 1960-Present” where he suggests that Landscape Urbanism is not so much applicable as a design strategy or particularly useful in looking at the landscape itself but instead offers a “design ethic” — a way of doing which privileges certain values, norms, assumptions and methods, and which treats particular problems in particular ways. This ethic requires a “design ethos” to which Hight turns to the Foucaultian theory of the disassembled self and Deleuze and Guattari’s body without organs. For Hight, both the disassembled body and the body without organs reflect a “freeing, distancing or more precisely, [a] disassembling of the essentialist humanist subject.” Landscape Urbanism, as Hight is careful to make clear, does not attempt to show us how to interact with what we call landscape or urbanism but…disassembles the identity of the architect and the urbanist and opens their fields of knowledge to ‘other’ monstrous potentials.

IMPOSTER: The wolf in sheep’s clothing is among the oldest models of monstrosity. In this model we identify a behavioral, or action based concept of monstrosity within architectural form, something that behaves other than how it appears. One example of such a monster can be found in the work of Reyner Banham, specifically his critique of Modernism understood from the perspective of environmental performance and temperament. In his 1969 book The Architecture of the Well-tempered Environment Banham claims that despite Modernism’s stated tenants of a rationalized functional architecture, its objectives were driven in many ways by a specific spatial and aesthetic agenda. Buildings were to look like the machine they claimed to be employing, rigorous, hard edged and taught, resulting in the thinning of walls, an increase in glazing and an often highly synthetic relationship with their external environment. Modernism rejected any idea of a vernacular to instead embrace the machine aesthetic of the prototype, which lacked any perfromative purpose inherent to all industrialized machines. Banham observes the implications of this inability to perform results in the further development of environmental control by mechanical means, dominated of course by the great equalizer air-conditioning.

The hairy architecture of MOS.

In his text Banham does provide an alternative approach to the hangover of Modernism’s monstrous relationship with its environmental performance and it may serve us well to mention it here. He describes that the productive integration of technological power into the architectural project requires a double knowledge of the behavior of such technology and a knowledge of the environment into which it is being applied, however most importantly the architect must recognize that these two sets of characteristics are together mutually modifying [Reyner Banham, The Architecture of the Well-tempered Environment. [Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1969], pp. 275]. In this relationship it is not that architecture benefits from the outright control of the environment, but rather by an active balance between its relevant learned intelligence and the productive integration of new technologies. This dual approach provides the most likely chance for innovation and effectiveness within a changing environment and results in a project that may appear outside the norm.

ALIEN/ANIMAL: An Alien or Animal Architectural Monstrosity might simply be something that is radically an-architectural in a classical sense. These collaborations will be strange beasts of buildings, perhaps semi-living, and more than likely unrecognizable as human constructions. They are formed through the invitation of alien or non-human participation. Temple Grandin, a prominent researcher in the field of animal psychology, ethology and behavior and has completed several designs for ranching and animal processing facilities. She is one of few professionals actively working to design spaces with the well-being of animals in mind — and she is not an architect. Temple’s expertise lies mainly in animal psychology and her spaces are designed to help soothe an otherwise anxious animal on the way to processing. Her designs address an animal’s field of vision and physical position relative to other animals, along with peripheral objects that may excite them. The designs are often highly curvilinear to minimize peripheral vision and convey a sense to the herding livestock that they are in fact returning home and not to the slaughter.

Curvilinear Cattle Corral

Anton Garcia Abril has completed a different kind of cross-species collaboration with The Truffle, an exercise in Human/Bovine architectural collaboration. In this project Mr. Abril invited a local cow to assist in the construction of his guest house. The project is literally a product of the combined efforts and patterns of two distinct species – marks of both are embedded into the structure. In the Truffle Mr. Abril has extended not only that which is proper to man (the hand) to another animal, but through an openness of invitation has endowed this other being with a sense of handedness — the essence of monstrosity.

Anton Abril, The Truffle

CONCLUSION:

The Monstrous Architecture presented here stands at the extreme bounds of current architectural theory and practice. The projects themselves are extreme — the theory they express is perhaps even more so. A Monstrous Architecture, other than its aesthetic qualities must be monstrous in the Heideggarian sense — in its openness to un-handed agents. Only then will the demonstrative nature of architecture, as a sign of humankind as a thinking being, transcend its earthly nature of grasping and controlling and open itself to give the gift of handedness. In practical terms this merely means that we are called upon to take on the small (maybe not so small) task of re-inventing architecture.

The Monstrous Architecture, must not be formulated as a negative thesis against the current status but as a positive exploration of new collaborations, wide-ranging dialogs and poly-species environments. The work collected here has attempted to show that monstrous conditions can occur at a variety of scales and applications. There is an obviously fantastic quality to some of the projects but designers and thinkers such as Temple Grandin, Anton Garcia Abril, James Corner or LTL each show that such prospects are not completely out of the realm of the possible. Monstrosity and humankind as a Monstrous Sign, once confronted, negotiated and resolved, can provide a strong framework through which we can reformulate the apparatus of our global colonization. We need not look too far for conceptual guidance — Heidegger, Donna Harraway, Jacques Derrida and Cary Wolfe among others have outlined our path. What we need now are firm design decisions. It is the challenge of the builders, those who define and daily reaffirm certain proscribed ways of life, to set this new discourse into motion.